An Introduction to Lindenmayer Grammars

15 December 2020

Created: 2020-12-15

Updated: 2020-12-20

Topics: Computer Science, Biology, Cognitive Science, Physics, Mathematics, Philosophy, History

Confidence: Probable

Status: Still in progress

Rewriting Systems Sequence - Part 0

TL;DR - An introduction to abstract rewriting systems, lindenmayer systems, and formal grammars, exploring the philosophical motivation, mathematical theory, practical applications, and major assumptions.

Feel free to skip the background + theory and head to the next part of this sequence of articles where we implement Lindenmayer systems in Python to generate plant-like structures.

- Rewriting Systems Sequence - Part 0

- Motivation

- Theory of Rewriting Systems

- Lindenmayer Systems

- Applications

- Moving Forward

- Resources

Motivation

Could simple rules govern how living structures build themselves out of non-living structures? Can these simple rules generate much of the biological, chemical, and physical phenomena we see around us? In other words, can these complex systems be reduced to just the interaction of simple rules? More generally, could these rules allow us to blur the arbitrary Newtonian distinction made between objects and the background from which they are situated in, such that the objects are composed of the background itself?

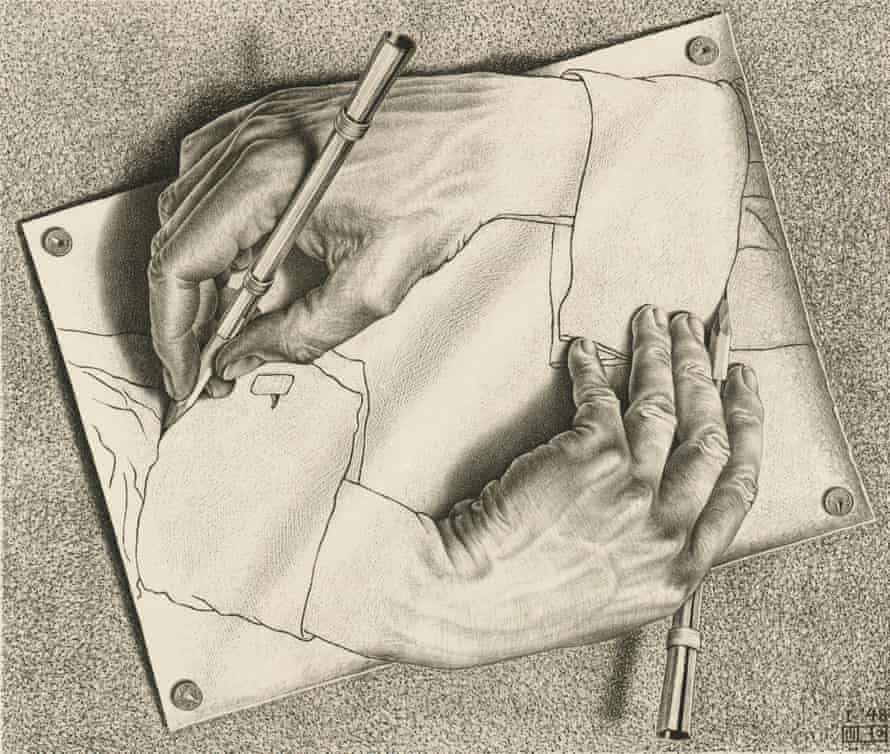

Drawing Hands is a lithograph by the Dutch artist M. C. Escher. It is referenced in the book Gödel, Escher, Bach, by Douglas Hofstadter, who calls it an example of a strange loop.

Drawing Hands is a lithograph by the Dutch artist M. C. Escher. It is referenced in the book Gödel, Escher, Bach, by Douglas Hofstadter, who calls it an example of a strange loop.

Questions like these might help prime your intution for the Church-Turing-Deutsch Principle, which roughly states that every finitely realizable physical system can be perfectly simulated by a universal computing machine operating by finite means. It is effectively viewing the various systems and phenomena found in Nature as a sort of computation being enacted out, a type of Digital Physics or Pancomputationalist perspective.

It is key to note that we are not envisoning all of Nature as literally a computer like you might have on your desk or in your pocket, but rather trying to be more general and viewing Nature as following a well-defined set of steps such that any one particular system or special configuration of molecular matter is just a particular instantiation or substrate for which a more general mechanistic set of relations or rules is being played out on, very similar to how you can do the addition of 5+4=9 with rocks, with sticks, or on a digital calculator, the inputs and outputs are always the same. In other words, it is the claim that this set of relationships or rules can be imposed on any particular physical material system and the computation would be the same. Such a broad conception of computation tends to be captured by the phrase substrate independence or multiple realizability.

A Conus textile shell similar in appearance to Rule 30. Rule 30 is an elementary cellular automaton that displays complex aperiodic, chaotic behavior, similar to patterns like that of this shell.

A Conus textile shell similar in appearance to Rule 30. Rule 30 is an elementary cellular automaton that displays complex aperiodic, chaotic behavior, similar to patterns like that of this shell.

With that said, without necessarily strongly claiming the truth of such a principle, in this series of articles we will instead seek a more epistemically humble and pragmatic perspective for now, and limit ourselves to the study of a computational concept called Rewriting Systems (RS) and the implications they could have in modeling various phenomena.

Theory of Rewriting Systems

We all learn that equations are composed of a string of symbols or terms written down. For example, in the equation 2+3+4=9, we have seven different symbols or terms: ‘2’, ‘+’, ‘3’, ‘+’, ‘4’, ‘=’, and ‘9’. We know that we can simplify this formula by replacing certain subterms in this formula with equivalent terms, namely by replacing the three symbols of ‘2+3’ with the single symbol ‘5’, etc, eventually boiling down to the expression ‘9=9’.

In essence, what we are doing above is rewriting certain terms as other terms, and we are doing this in an attempt to simplify things. But what if we were to reverse our direction and generate terms by expanding out our expressions? Or what if we didn’t necessarily care about a particular direction, but rather we just simply keep rewriting or replacing certain combinations of terms with other terms and then see how the dynamics of our system eventually play out?1

For an example of rewrite systems in action, let’s imagine we have a set of red and blue candied fish laid out in a horizontal line on the table in front of you. Let’s represent that system by the following:

red red blue blue red red blue blue

And let’s set our rewrite rules as follows:

blue blue -> red

blue red -> blue

red blue -> blue

The above basically states that whenever we see two blue fish in a row, we can replace them both with a single red fish. Similarly, whenever we see a blue fish and then a red fish, we can replace them both with a single blue fish, etc. The following shows what happens to our line of fish when applying any one single rule at that stage.

red red blue blue red red blue blue

red red blue blue red blue blue

red red red red blue blue

red red red blue blue

red red blue blue

red blue blue

blue blue

red

We can see that with an even number of blue fish, the sequence will always end in red fish. We can modify the rules so that the outcome is totally independent of the particular rule we choose to apply when. We can also modify the rules so that as mentioned before, instead of having every rule simplify the line of fish, some rules can generate new fish, etc. Additionally, we can modify our rules so that they take the form of a template such as,

blue … blue -> red …

where anytime we see an ellipsis, we can fill in that with any number of fish as long as the other ellipsis is the same amount. These variations upon rules can continue on and on.2

To help us generalize, let’s define a few properties of rewrite systems:

1) Normal / Canonical / Standard Form: This basically means that our object composed of a sequence of terms cannot be simplified any further. An object is said to be weakly normalizing if it can be rewritten somehow into a normal form, that is, if some rewrite sequence of steps starting from it cannot be extended any further. An object is said to be strongly normalizing if it can be rewritten in any way into a normal form, that is, if every rewrite sequence starting from it eventually cannot be extended any further.

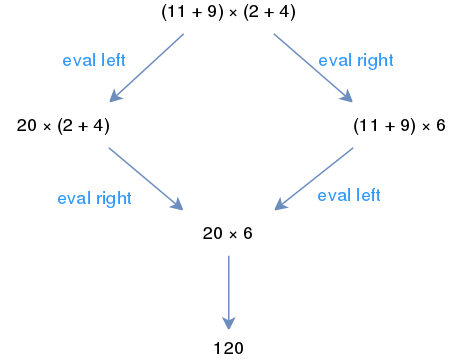

2) Confluence: This describes which terms can be rewritten in more than one way, to yield the same result. For instance, let’s take our rules of addition and multiplication in arithmetic. We can either evaluate (or rewrite) our equation starting from the left or starting from the right, as shown in the below example. Since both routes evaluate to the same thing, then we can say that our arithmetic rewriting system is confluent. In other words, no matter how two paths diverge from a common ancestor (w), the paths are joining at some common successor.

In arithmetic we can either simplify our expression via the left path or the right path.

In arithmetic we can either simplify our expression via the left path or the right path.

3) Terminating / Noetherian: A rewrite system (RS) is terminating or noetherian if there is no infinite chain of rewrite steps. In other words, in a terminating RS every object is required to have at least one normal form that it reduces to. This property is crucial if we are to use a RS for computation or as a decision procedure for the validity of identities.

4) Convergent: If our RS is terminating AND confluent, then we can also call it convergent. In other words, every object has a unique normal form.

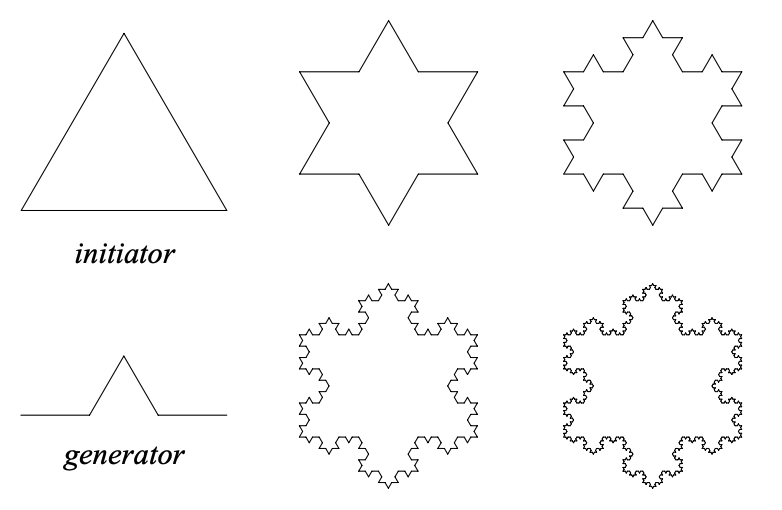

Rewriting systems can take make forms and act on a number of different objects. If acting on polygons, they can be used to produce fractal images like the Koch Snowflake where one has two shapes, an initiator and a generator,

Construction of the snowflake curve

Construction of the snowflake curve

The first seven iterations applying the generator

The first seven iterations applying the generator

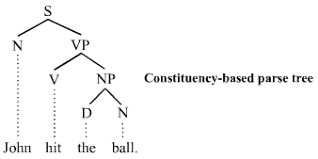

Or when the objects are strings in a natural language, they can be used in linguistics as models of grammatical structure like Chomsky’s work in formal grammars,

A generative parse tree: the sentence is divided into a noun phrase (subject), and a verb phrase which includes the object.

A generative parse tree: the sentence is divided into a noun phrase (subject), and a verb phrase which includes the object.

Or when the objects are arrays, like in Conway’s Game of Life where they form the cornerstone of the diverse phenomena witnessed,

An interactive implementation of John Conway's Game of Life built in WebGL by Sam Twidale.

An interactive implementation of John Conway's Game of Life built in WebGL by Sam Twidale.

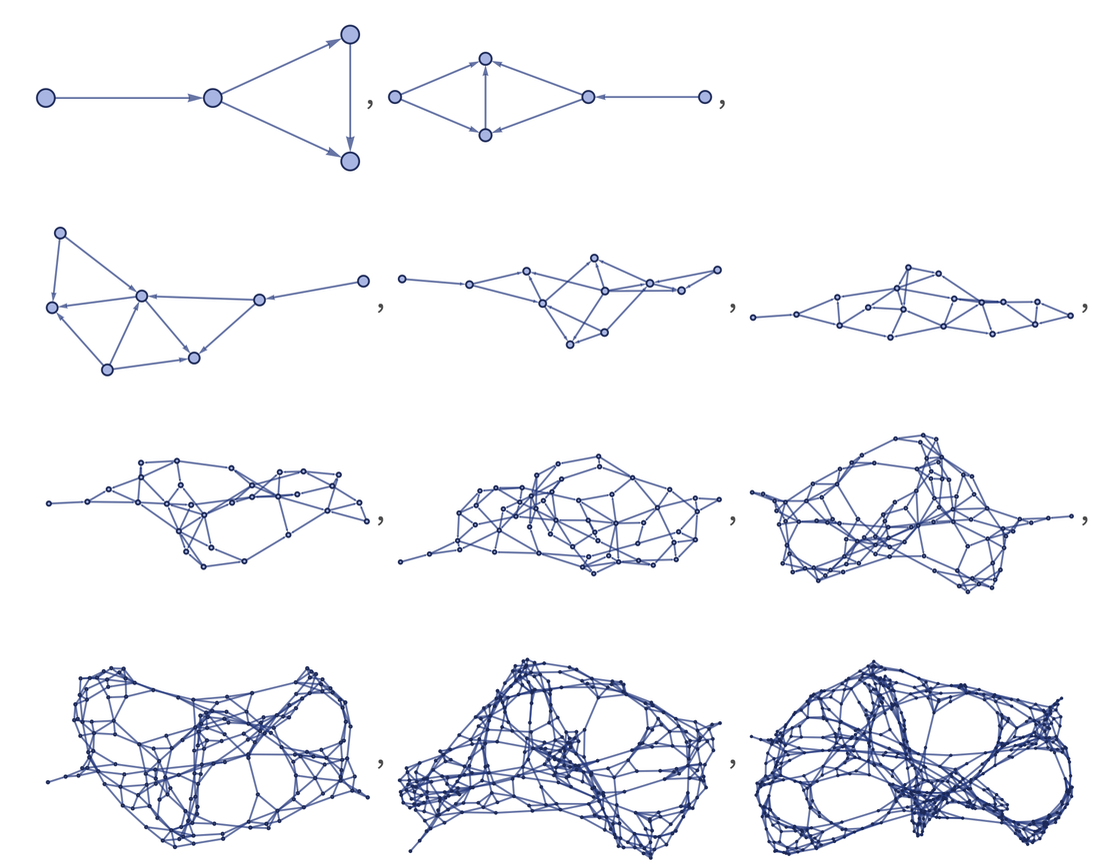

Or when the objects are graphs, like in Stephen Wolfram’s Physics Project where he is trying to create a new fundamental theory of physics and derive physical laws from the bottom-up (while other people are also using graph rewriting systems to analyze causality in molecular systems),

With all that said, we will limit ourselves to the study of a particular type of rewriting system called a Lindenmayer System…

Lindenmayer Systems

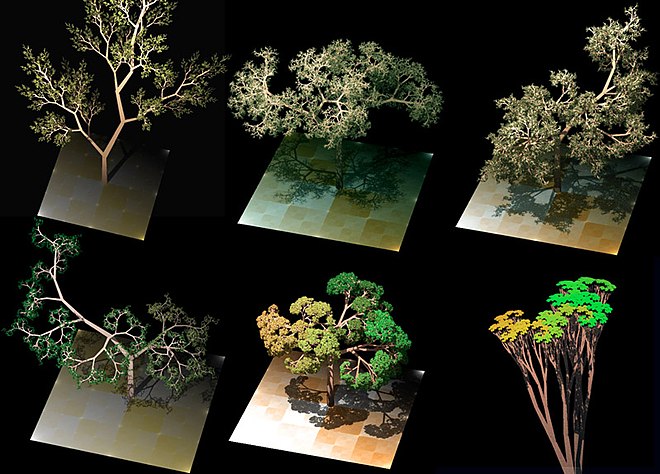

L-system trees form realistic models of natural patterns.

L-system trees form realistic models of natural patterns.

A Lindenmayer System (sometimes called L-grammars, parametric L-Systems, or L-systems for short) is a specific type of rewrite system. L-systems were created by a Hungarian theoretical biologist and botanist named Aristid Lindenmayer in 1968, independent of work done in symbolic dynamics at the time. Aristid originally worked with yeast, fungi, and algae, and studied how they grew into various filamentous patterns, later moving on to more advanced organisms like plants.

'Weeds', generated using an L-system in 3D.

'Weeds', generated using an L-system in 3D.

L-systems grew in popularity due to the beauty of how simple recursive rules can lead to self-similar objects and thus fractal-like forms resembling seemingly complex shapes of organisms in nature like grasses, ferns, and trees.

Recursively growing a plant.

Recursively growing a plant.

In particular, an L-system is an RS that can be defined as the tuple:

G = (V, ω, P)

Where that tuple consists of 3-4 things:

1) An Alphabet, V, of symbols that can be used to make strings (a sequence of characters). This alphabet in turn consists of symbols that can be replaced (variables) and symbols that cannot be replaced (constants or terminals). Furthermore, we let V* represent the set of all words over V, and V+ represent the set of all non-empty words over V.

2) An initial Axiom string, ω, from which we begin construction from (similar to our starting line of colored fish from above). It defines the initial state of the system.

3) A collection of Production Rules or Productions, P, that expand each symbol into some larger string of symbols. Specifically it is a set of rewrite rules that can be recursively performed to generate new symbol sequences. In turn, each production rule consists of two strings, the predecessor and the successor, that string which is to be replaced and that string which it is replaced by respectively. If no production is explicitly specified for a given predecessor a ∈ V , the identity production a → a is assumed to belong to the set of productions P.

4) A Mechanism for translating the generated strings into geometric structures. (This is a weak requirement and only used in the case of visualization or other applied purposes)

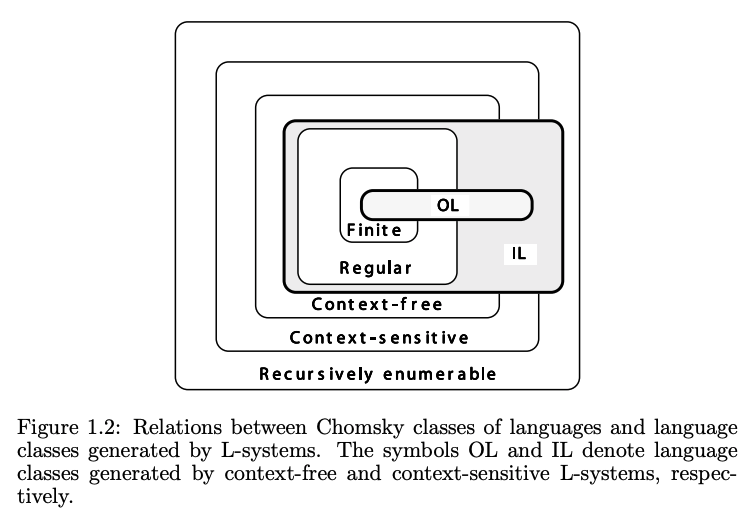

From here we apply the production rules to the axiom in an interative fashion, with as many rules as possible being applied simultaneously per iteration. This latter requirement of applying as many rules as possible per iteration rather than applying only one rule per iteration is what separates L-systems from formal languages generated by formal grammars3, and that is why they are sometimes called parallel rewriting systems. Thus, L-systems are strict subsets of languages. This parallel nature was originally meant to capture the cell divisions that occur in multicellular organisms, where many divisions can occur at the same time.4 This is a key distinguishing feature going forward.

Similar to before with the more general rewrite systems, our more specific L-systems have 2 additional properties:

1) An L-system is Context-Free if each production rule refers only to an individual symbol and not its neighboring symbols. If instead a rule requires that it check not only that single symbol, but also that of its neighbors, then we say that it is context-sensitive.

2) An L-system is Deterministic if there is exactly one production rule per symbol. If instead there are several rules that can apply to a certain symbol and we choose a particular rule according to some probability each iteration, then we call the L-system stochastic.

If an L-system is both deterministic and context-free then it is called a DOL System. It also might be key to note that rewriting systems are not necessarily algorithms! They can however be turned into algorithms if they have the following conditions: we can apply the rules in a deterministic way, use a reduction strategy showing how we can simplify a complex expression by successive steps, and finally

showing that there is a unique normal form (ie - a unique set of terms that can no longer be reduced) that can be found for each word such that the algorithm will terminate.

Applications

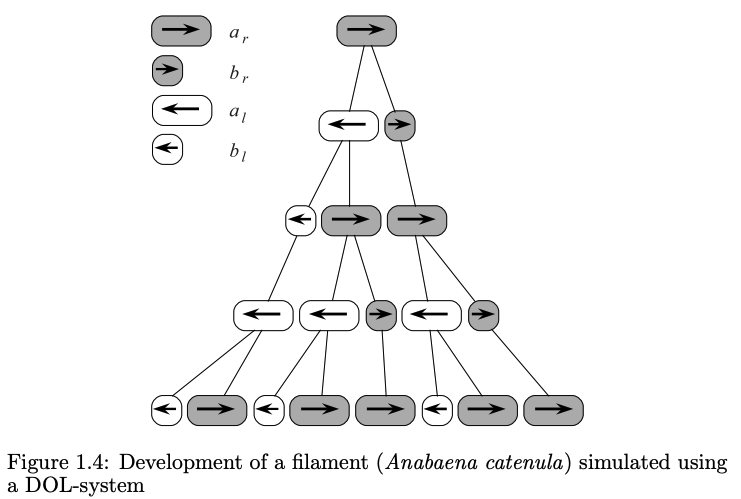

Cells in the filament divide in a asymmetric manner: one of the daughters is longer than the other. Additionally, the two possibilities for ordering the daughters (small-long or long-small) obey a specific rule.

Cells in the filament divide in a asymmetric manner: one of the daughters is longer than the other. Additionally, the two possibilities for ordering the daughters (small-long or long-small) obey a specific rule.

So let’s investigate how Lindenmayer originally used his L-systems to model the growth of algae. We can see that he defined his systems components as follows:

Alphabet: A B (both variables, no constants)

Axiom: A (what we start with)

Rules: (A → AB), (B → A)

At each stage of iteration n we can see that this produces the following:

n=0: A (start axiom/initiator)

n=1: A B (initial single A spawned into AB)

n=2: A B A (A → AB), (B → A)

n=3: A B A A B

n=4: A B A A B A B A

n=5: ABAABABAABAAB

n=6: ABAABABAABAABABAABABA

…

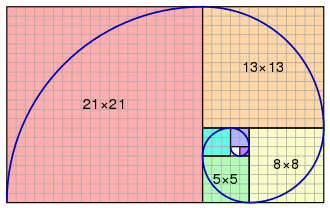

What’s interesting to note is that with these rules if we count the length of each string we get the Fibonacci sequence of numbers. That is why this sequence is sometimes called a sequence of Fibonacci words.

1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89 …

A tiling with squares whose side lengths are successive Fibonacci numbers: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 and 21. An approximation of the golden spiral is created by drawing circular arcs connecting the opposite corners of squares in the Fibonacci tiling.

A tiling with squares whose side lengths are successive Fibonacci numbers: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 and 21. An approximation of the golden spiral is created by drawing circular arcs connecting the opposite corners of squares in the Fibonacci tiling.

The formalism above is used to capture and simulate the notion of the development of a fragment of a multicellular filament such as that found in the blue-green bacteria Anabaena catenula and other various algae,4

Where the symbols a and b represent the different states of the cells (their sizes and readiness to divide), and the subscripts l and r specify the positions in which daughter cells of type a and b will be produced. This particular mapping was chosen because it was observed that underneath a microscope, the filaments appear as a sequence of cylinders of various lengths, with a-type cells longer than b-type cells.4

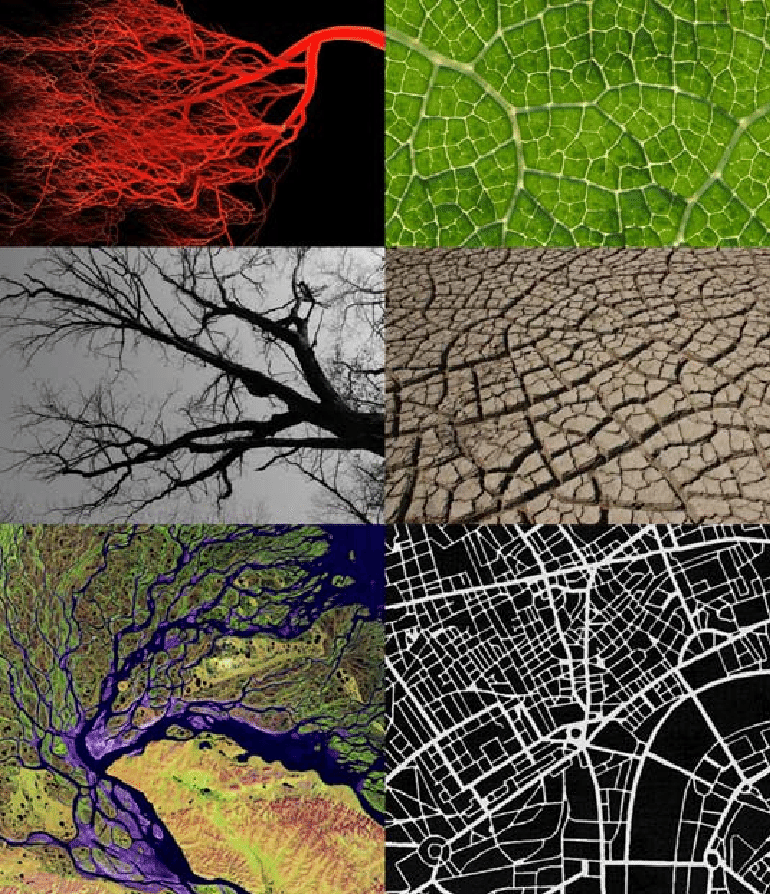

So what other phenomena can be captured by this particular L-system formalism? Because L-systems were originally intended to model the growth of systems in a directed, recursive fashion, we know that they can be represented visually by directed graphs in a tree-like structure. As such they can be used to model dendritic or arboreal geometries found in nature.

Blood vessels, winter tree, Amazon River delta, leaf veins, cracked earth, and a city plan

Blood vessels, winter tree, Amazon River delta, leaf veins, cracked earth, and a city plan

These tree-like structures are rather ubiquitous in nature. Intuitively, many biological structures like blood vessels, neurons, mycological growth, slime-molds, etc can at the very least be visually said to follow this scheme.

Slime mold is a name given to several kinds of unrelated eukaryotic organisms that can live freely as single cells, but can aggregate together to form multicellular reproductive structures. This colony organism can even solve mazes.

Slime mold is a name given to several kinds of unrelated eukaryotic organisms that can live freely as single cells, but can aggregate together to form multicellular reproductive structures. This colony organism can even solve mazes.

Similarly, in physics we have lightning and Lichtenberg figures,

A Lichtenberg figure is a branching electric discharge that sometimes appears on the surface or in the interior of insulating materials. It is an example of natural phenomena which exhibit fractal properties. This particular video was taken by Evan Blomquist from *Electrostatic Wood*.

A Lichtenberg figure is a branching electric discharge that sometimes appears on the surface or in the interior of insulating materials. It is an example of natural phenomena which exhibit fractal properties. This particular video was taken by Evan Blomquist from *Electrostatic Wood*.

And because of the ubiquity of arboreal phenomena in nature5, we can see that with just a few tweaks to the underlying representative data structure and topological embedding, we can perhaps take on a new perspective6 of viewing a portion of these phenomena as toroidal graphs (graphs that can be embedded onto some toroidal topology). Perhaps more speculatively, this perspective might grant us a few key insights into the study of the transitions between living systems and non-living systems and the development of a singular Identity that persists through time.

Moving Forward

In the next article of this series, we’ll lean into the more practical side, and dive into the nitty-gritty showing how to experiment and simulate L-systems in Python to generate plant-like structures.

Resources

-

As a side note, rewrite systems are known to possess the “full power of Turing machines and may be thought of as non-deterministic Markov algorithms over terms, rather than strings”2. ↩

-

Handbook of Theoretical Computer Science, Chapter 6: Rewrite Systems by Nachum Dershowitz and Jean-Pierre Jouannaud. This provided much of the theory behind the theory of Rewriting and abstract rewrite systems. It specifically goes into depth on ARSs from algebraic, logical, and operational perspectives. ↩ ↩2

-

Math StackExchange question: What are the relations and differences between formal systems, rewriting systems, formal grammars and automata? ↩

-

The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants by Przemysław Prusinkiewicz (director of the Computer Graphics group studying Fibonacci numbers and modeling using grammars) and Aristid Lindenmayer(a theoretical biologist studying sequence generators). This textbook is based off Lindenmayer’s original notes discusssing the theory and practice of Lindenmayer (L-)Systems for modeling plant growth. It provides much of the material from which I “draw” from (heh) for this sequence of articles. Seriously though, I HIGHLY recommend at least glancing through this book. It has some beautiful diagrams and the explanations are written in a simple, easy to understand language. It is also incredibly practical and beginner-focused with its explanations given in the Python Turtle-language. Any theory or math is either explained really well or kept to a minimum. I really appreciate the authors for writing such an awesome resource :) ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

While phenomena possessing tree-like geometries seem to be common due underlying feedback mechanisms, non-linearity, and evolutionary drives towards data compression using iterative schemes, it should be noted that this is still a drastic simplification for the purposes of mathematical modeling. To add more nuance and complexity to the model, we should also take into account the extra energetic and biomechanical demands and constraints upon growth which shapes branching arrangement. See here for a discussion on the mechanical properties of a tree and the efficiency of the branching pattern. ↩

-

Indeed, although toroidal graphs are more complicated than simple planar graphs, they have found many applications, especially since many computer networks have a toroidal structure. See here which discusses graph embedding onto toroidal topologies, in addition to talking about Kuratowski’s theorem which is a test of graph planarity. ↩