Book Review - The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants

29 November 2020

Created: 2019-11-29

Updated: 2020-12-31

Topics: Computer Science, Biology, Cognitive Science, Physics, Mathematics, Philosophy, History

Confidence: Certain

Status: N/A

TL;DR - My review of Przemyslaw Prusinkiewicz and Aristid Lindenmayer’s book exploring the computational modeling of plant structures using parallel rewriting systems. 5/5

Cross-posted from my Goodreads reviews found here.

Required Reader Level

Accessible to a motivated high school student. No further knowledge is needed other than basic algebra 2 and a smidgen of trigonometry. To be able to implement the concepts in here, a rudimentary working-level knowledge of Python or some other programming language is best, though the authors walk you through partial pseudo-implementation in Turtle which is a pre-installed package that comes with Python. Alternatively, you can stick to just the Production Rules and enter them into an online L-system generator which requires zero programming.

With that said, a person who has studied the fundamentals of computer science would get a lot more out of this. Common discrete mathematics concepts like string manipulation, recursion, and elementary graph theory would be really useful. Botany and Biology-adjacent majors would love this book as the authors lead you by the hand through every concept. Nothing is too mathematical (in fact, I’d say there are no typically scary equations unless you’d want to dive more into animation and 3D modeling). As a disclaimer, I myself am trained in the biological sciences with hearty servings of computer science, mathematics, and philosophy. Anyways, other than that I’d also recommend checking out the other sources mentioned at the end of this review to complement your reading :)

Personal Thoughts

I was coming at this book hoping to like it and I came out of it absolutely loving it! In fact, it’s being added as one of my all-time favorite textbooks for self-study. My main motivation in reading this was dual-purposed: to understand what L-systems were from both an intuitive theory perspective and how to practically implement them in a programming language.

For those that aren’t aware, the main topic of this book is something called a Lindenmayer (L-)System which is a type of abstract rewriting system. L-Systems basically are composed of a string of character(s) that are fed into a series of rules that replace those character(s) with other combinations of character(s), ie - “rewriting”. This is then done over and over and over again, with each round of output being fed into the next round as input to generate a long string composed of complicated combinations of characters. Each character is then mapped to some logical operator, geometrical movement, biological mechanism, or physical phenomenon, etc.

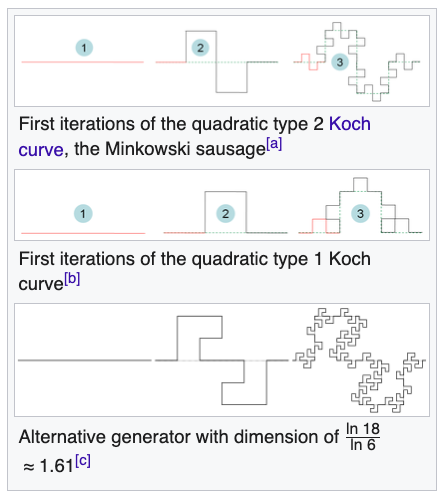

How each part of the Minkowski sausage is just a smaller version of the previous stage.

How each part of the Minkowski sausage is just a smaller version of the previous stage.

Ultimately, this is all done to show how seemingly complex structures can arise out of just the interaction between a few simple rules. Lindenmayer himself was originally a theoretical biologist interested in mathematically modeling the variety of complex structures of plants, and the other author Prusinkiewicz excels in the graphical modeling and programming part. Together they make a formidable pedagogical team. I myself am interested in this from an Artificial Life, Complexity-Theoretic, and Digital Physics perspective. Other notable interests that were fulfilled by this book were the mentions of the connections between fractals, phase-effects + dynamics, and cellular automata.

Turtle drawing an n=2 Minkowski Island.

Turtle drawing an n=2 Minkowski Island.

Overall, the authors start from the bottom-up, building out your basics of how abstract rewriting systems work, then moving on to showing you how we can map these symbols to some geometrical representation, and then finally extending the representation by layering on some more structure, getting more complex as you move through the chapters. This is all accompanied by lots and lots of pictures and diagrams to aid your intuition. This latter point proved really helpful, especially in helping build the visual intuition needed to convert strings of characters to tree-like graph structures. My absolute favorite section was learning how L-systems could be used to represent signal propagation and other similar biophysical phenomena like diffusion. This was the main piece of meat I was after due to its wide-ranging modeling applicability throughout nature and I’m glad the authors explained this well.

Chapter Breakdown

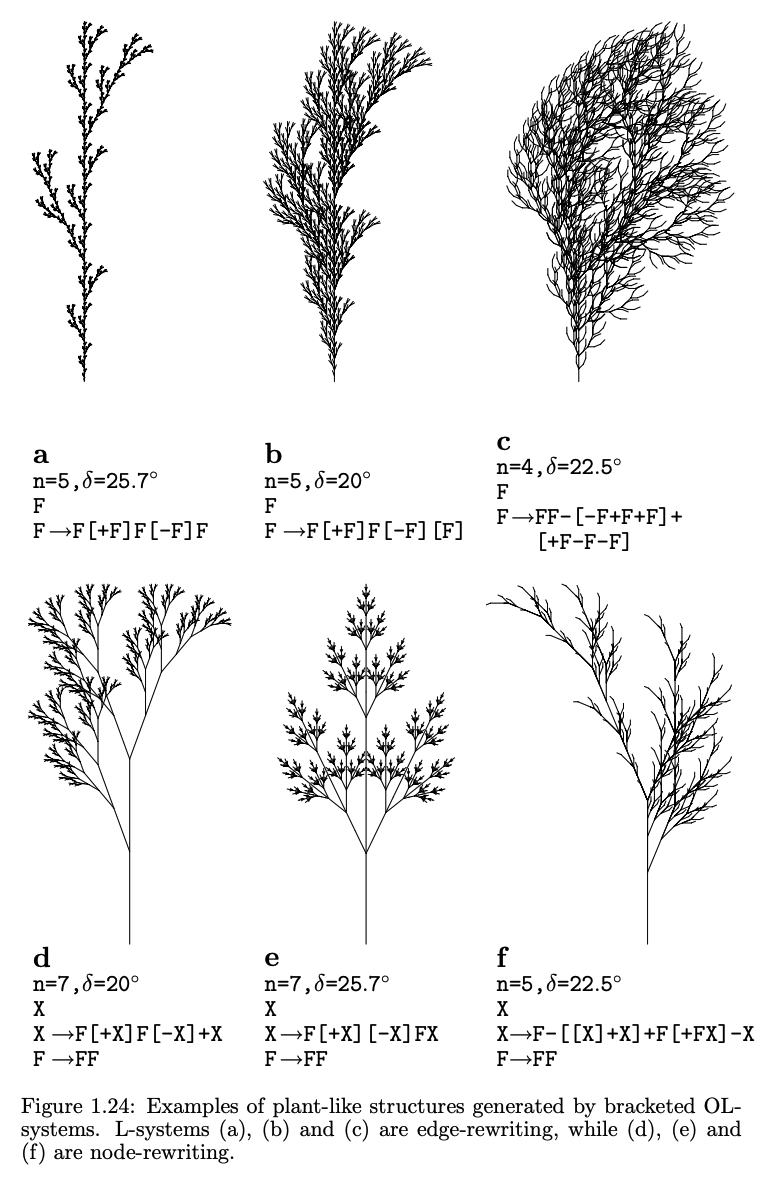

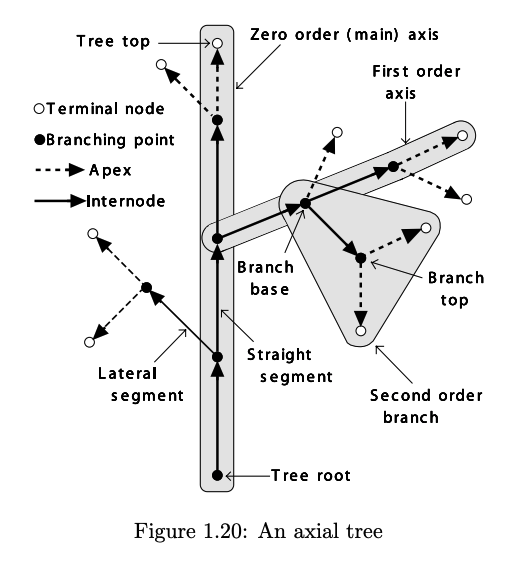

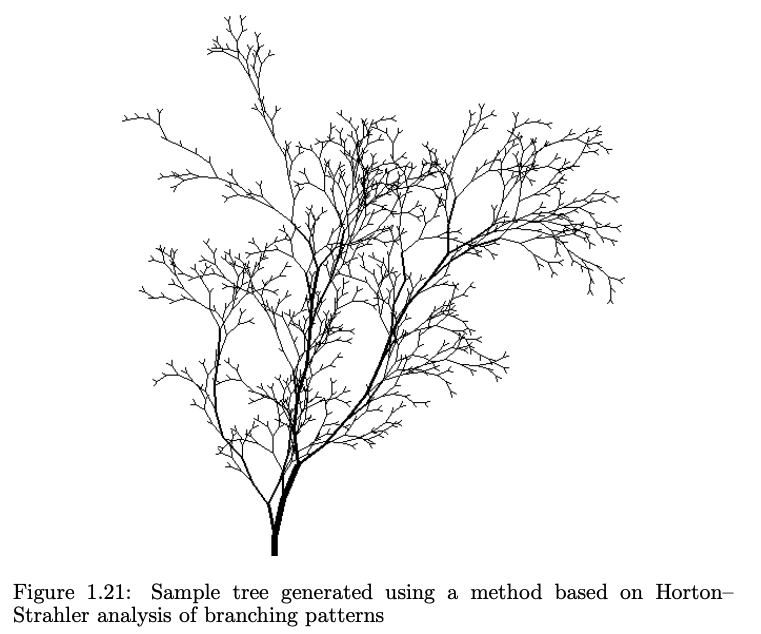

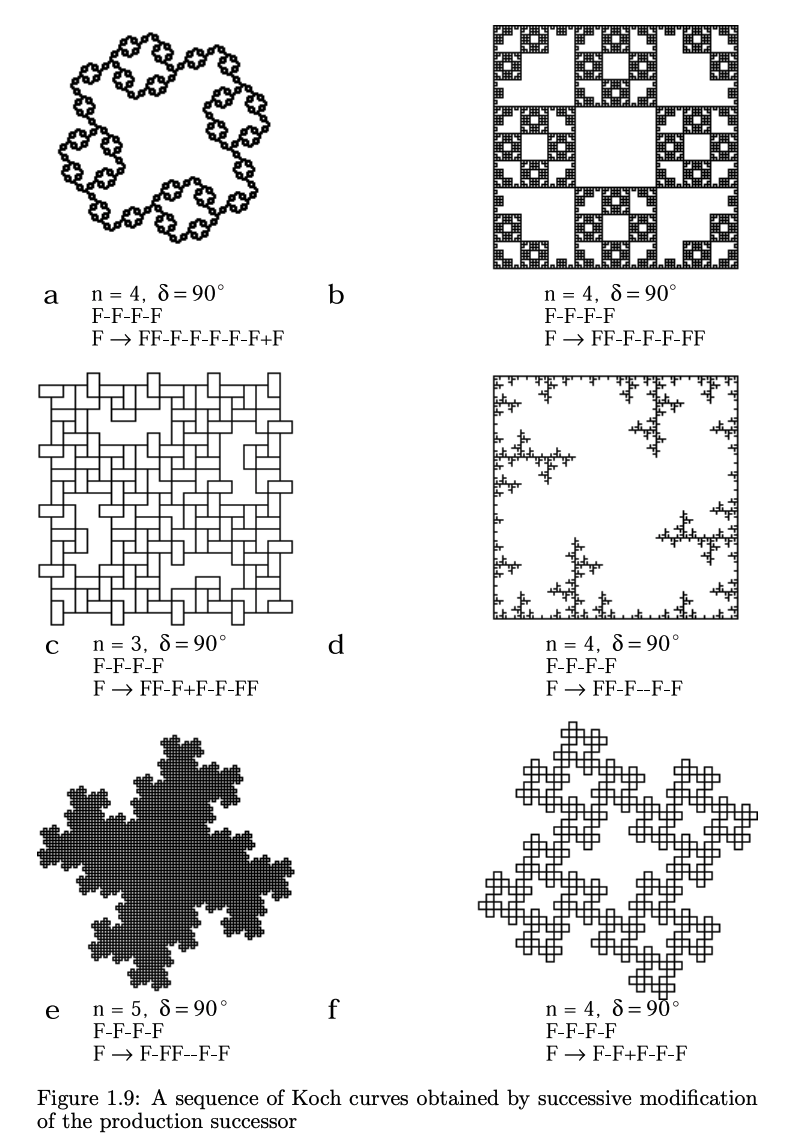

Ch 1: The authors introduce you to the basic theory behind rewriting systems as string replacement mechanisms. They start off with a visually intuitive fractal representation, and then move on to how we can practically draw this with Turtle. They go over the differences between node + edge rewriting, 3D modeling, axial trees, using push-pop stack mechanics (called “bracketing”), adding stochastic rules, differences between context-free and context-sensitive grammars, adding growth functions, and finally operating on parameters (allowing real-valued numbers). Overall, as a beginner if you only read this chapter you would have already gotten your money’s worth of the time you invested. This is probably the single most important chapter as it gives you the fundamentals to start exploring things on your own. And while this first chapter builds itself up in a linear fashion, after this the chapters get somewhat topical and modular, so you can skip and jump around to whatever serves your interests best if desired. With that said, I basically just read the entire book linearly from start to end. Everything else is just icing on the cake from here.

From pg. 25 of *The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants*.

From pg. 25 of *The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants*.

Ch 2: In this chapter they move on to approaches that emphasize the interactions between parts of the growing structure. Such effects like adding differences in girths to trunks versus branches/limbs, adding the effect of gravity to some branch plane, adding various tropism effects (like light or nutrients), etc. This section is probably the most important if you are desiring models that are more physically realistic in an artificial setting.

From pg. 22 of *The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants*.

From pg. 22 of *The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants*.

Ch 3: Besides the first chapter, this section is one of my favorites. It goes over how to model biologically relevant phenomena like the space-time relation between different plant parts (phase effects) and differential growth capabilities of different sections of the plants. If you are creative enough, this allows you to model some really cool stuff like the differences between cell types and cell lineages as well as the consequences of herbaceous / non-woody plants versus woody plants. This is also where we can now model the effects of growth hormones (which if you’ve studied plants you know there are a wide variety of!) and cool compound flowering structures / inflorescences.

From pg. 22 of *The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants*.

From pg. 22 of *The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants*.

Ch 4: This chapter was a bit more mathematically challenging, but well-rewarding. In it the authors go over the plant phenomenon known as phyllotaxis which is the arrangement of leaves on a plant stem like alternating sides, whorled, and spiral patterns (which I thought was super neat! I mean, the vast variety of geometries of spiral structures of plants is one of the most beautifully geometric things mother nature has to offer here on Earth). Fibonacci numbers and floret designs feature heavily here. This is the chapter where my intuition was greatly enhanced regarding the connections between geometric packing problems / tiling, recursion, and number theory.

Ch 5: This chapter focused on specific plant organs like modeling leaves and petals. The geometry of “saddle-shaped” surfaces plays heavily here. This chapter was relatively short.

Ch 6: I was less interested in this chapter, but those of you who are into video games and computer animation might enjoy this a lot more. It basically focused on the animation of the stages of development of a plant. The parts I did find interesting were the introduction of growth functions since this plays a big role in how we can introduce concepts from dynamical systems at multiple perspectives of L-Systems (not only from the 1-dimensional topological string case for example, but also to the branching case). This chapter was short too.

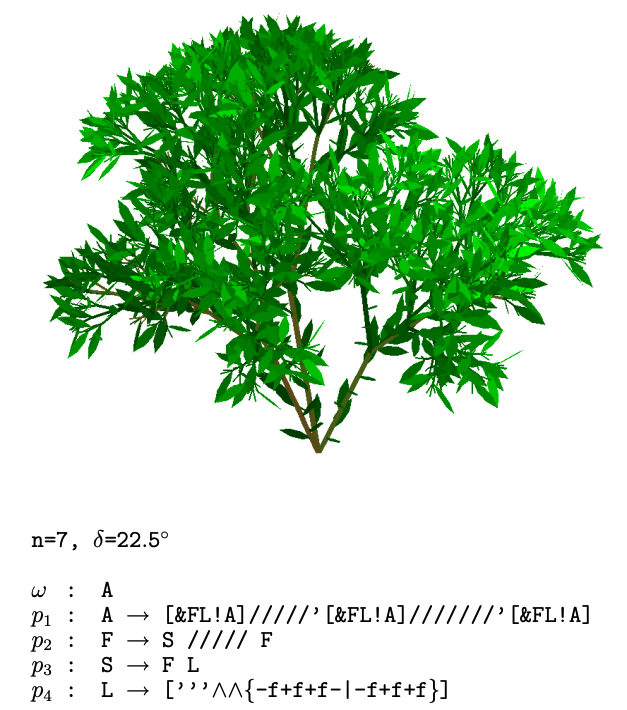

Showing a 3-dimensional bush-like plant from pg. 26 of *The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants.

Showing a 3-dimensional bush-like plant from pg. 26 of *The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants.

Ch 7: This chapter might be more relevant to the botanist and cellular biologists, but it mainly had to do with modeling the different cellular layers of a plant. Tissue distinction and physical structure is no joke, and I think this chapter was the most mathematically challenging out of all the sections. It is also arguably the most physiologically realistic section from a physical structure standpoint. Everything from modeling laminar layers, to spherical cell layers, to 3D cellular structures is covered here. Again, I found this section the most difficult, and will have to probably read through it multiple times to understand it fully.

Ch 8: This chapter was really fun. It was basically a chapter entirely spent on how L-systems intersect with the study of fractals! Hausdorff dimensions were mentioned, self-similarity, iterated function systems, scaling, etc. Although it wasn’t mentioned, I was also reading about some Group Theory on the side as part of my self-studies in Abstract Algebra (so that I in turn can understand how important symmetry is to Noether’s invariant laws in physics) and I felt like this was the most relevant section to that. I was disheartened by how short it was, but oh well, haha.

From *The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants* pg. 10

From *The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants* pg. 10

*The Appendices, References, and Bibliography sections are also a treasure-trove for those that have yet to make it a habit to mine these sections for hidden gems. In this particular case, Prusinkiewicz’s lab offers some great (though dated) software packages that they’ve built, as well as the more important references to other papers that might prove useful for further exploring this material (or for contacts to future lab colleagues 😉)

Overall, although this book is intended to be about plants, I think if you are creative enough to see the implications beyond this you can start applying this broadly, as many fields feature arboreal or “tree-like” phenomena. With some careful tweaks I can see this being applied to model work in mycology, neuroscience(!), geology, and more.

Availability

This book is offered free online by one of the authors himself!!!

You can find the book here and the author’s lab team’s page here which offers way more resources for the curious-at-heart. In fact, if this book weren’t so pricey, I would love to get my hands on a physical copy of it. I’m now going to be recommending it to pretty much everyone I see, haha.

I’m also actually rather jealous I can’t take a class with this professor. From just his pedagogical style offered in this book, the amount of open-sourced tools and material he offers online, and his great teaching ratings, I think he’d be a really cool mentor and guide :)

Other

Some other things I think might complement your reading experience would be this online browser-based L-system generator here. This should allow the beginner programmers / coding-averse of you out there to enjoy this book by just typing in a few parameters into your browser and out pops the image of your L-system, without doing any programming on your own.

With that said, I would highly recommend you try and code things along while reading this. I think you would get a lot more out of your time invested in this book and come away with a stronger understanding of the material if you do this. And it’s not as difficult as one might initially think. In fact, I created two tutorials so far that bring newbies up to speed and I walk you through the entire aspects of the experience, starting from the philosophy (I have a soft spot for this, I know, haha), moving onto the recursion concepts, and then finally moving on to the coding it up in Python where I lead you by the hand and walk you through every line of code.

My first tutorial is An Introduction to Lindenmayer Grammars, and I follow it up with my second tutorial, Generating a Garden with Python. I also offer the code that I used to generate the L-systems that you can freely download so you don’t need to do any programming yourself! All of this was built with the help of numerous online resources that I also link to as well as this excellent textbook by these authors. In a way, they were written to not only consolidate my own understanding, but also as a love tribute to the book’s excellence.

Thank you to Prusinkiewicz and Lindenmayer and their team for creating a remarkably beautiful (in more ways than one) book!

Happy Gardening everyone :) 🌹🌲🌻🌿

Cover art created by Lioudmila Perry.